Sirens in the Cosmic Fugue

Create vessels and sails adjusted to the heavenly ether, and there will be plenty of people unafraid of the empty wastes. In the meantime, we shall prepare, for the brave skytravellers, maps of the celestial bodies – I shall do it for the moon, you Galileo, for Jupiter

––– Johannes Kepler, Letter to Galileo Galilei, April 1610

Cold War’s Celestial Chariots

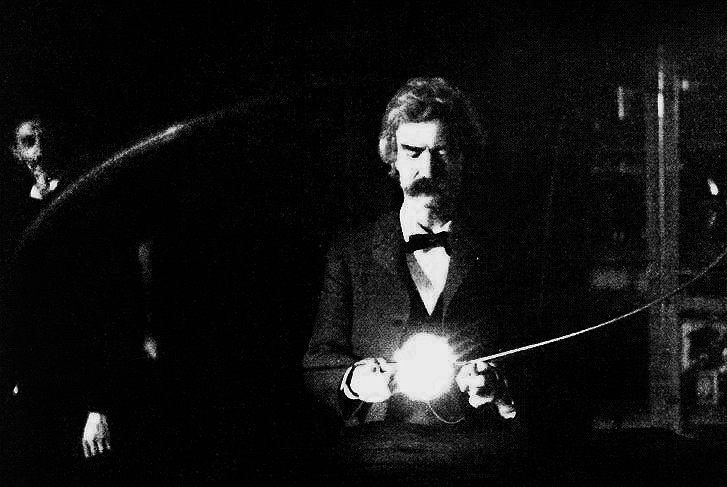

‘beep-beep’, a sound of wonder and disquietude reverberated, literally and figuratively; across the skies as even amateur radio operators tuned in to listen in on the transmissions @ 20.005MHz. The Pravda christened it as an ‘artificial moon’ one that had scaled up the terrestrial gravity well, which had bound humanity to this Pale Blue Dot. Alan Shepard had just graduated from the Naval War College. John F. Kennedy was still a junior senator from Massachusetts. Yuri A. Gagarin was an unremarkable Russian military pilot. While the ‘father of rocket technology’: Wernher von Braun was working on the Jupiter ballistic missiles. Little did these men know this unpretentious small sphere would manage to capture human imagination and paranoia: metastasizing in the global consciousness and cast a very large shadow indeed. A new era of exploration was about to dawn. It was the 4th of October 1957 and the Soviets had just launched the Sputnik.

humanity, got odyssey inside my DNA

The history of humanity has always hung onto a timeline of exploration. For millennia, since modern humans emerged in the horn of Africa we were wanderers. We meandered past vast landmasses, across forbidden seas and narrow straits, down rolling valleys in search of plentiful game and congenial climates. The impetus to explore has had unmistakable survival value. As the last ice age ended and the ice thawed, we settled down marking the beginnings of the Neolithic Age. We domesticated plants animals, and in turn they domesticated us.

Thenceforth empires have risen, developed, devolved and fallen, blood has been spilt in the name of gods, pharaoh and queen. As change came to define human history, the itch for exploration was one that was sempiternal regardless of ones ethnicity, ideology or geography. Phoenicians surveyed the Mediterranean Sea pushing through the Pillars of Hercules (Strait of Gibraltar) into the Atlantic. Polynesians settled on every habitable island in the Pacific till Hawaii traversing 16 million square miles of treacherous ocean guided by just the stars and the currents whilst Vikings touched the coast of modern day Canada half a millennium before Columbus. On the behest of Admiral Zheng He, Ming Era ocean going junks crisscrossed the Indian Ocean sailing as far away as Hormuz on the Persian Gulf and Aden on the Red Sea. The Age of Discovery saw Europeans (re)discover the New World subsequently circumnavigating the globe. In recent times, few of us have claimed the adobe of the gods of old soaring 400km up. We owe these feats to a restless few: irrepressible renegades drawn by a yearning that they could barely understand nor articulate themselves.

JFK and his Technocrats

It is a humbling irony that spaceflight—conceived in the tile cauldron of nationalistic rivalries and vitriol—was the harbinger of a shared human vision. Tremendous acceleration of the space programme in the 1960s, got humans to the moon before the end of that decade. John F. Kennedy as a president was lukewarm on committing to an aggressive space program before pivotal events in 1961. He was not a starry-eyed idealist enraptured with the romantic image of the final frontier in space nor consumed by dreams of a spacefaring civilization. On the other hand, he was a maestro of cold war rhetoric with a keen sense of Realpolitik in foreign affairs. Yuri Gagarin’s orbital mission aboard Vostok 1 coupled with the failed Bay of Pigs debacle, displayed the Kennedy administration’s technical and strategic incompetence as the power struggle over the ‘fluid battleground’ of the Third World tipped in the Soviet’s favour. United States’ security hinges as much on winning hearts and minds as it does on military might. Thus Kennedy in a bid to recapture leadership in space so as to project America’s soft power believed “that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth”. The challenge required the mobilization of resources on a national scale to develop and apply the pioneering technologies of their times. This in turn called for skilful management of administrative capacity, a responsibility that fell upon NASA and the Federal Government. A frontier narrative was sold to the media and the public by the administration subsuming arguments about the technology and economics of the program, and established a presumption in favour of massive commitments of the nation’s resources to manned space flight. The Cold War realities of the time, therefore, served as the primary vessel for an expansion of NASA’s activities launching the premier civil space effort to a broad consensus of support. ‘We came in peace for all mankind’ the lunar plaque placed by Apollo 11 crewmembers read while megatons of explosives were being dropped in Vietnam.

Children of Apollo

The Apollo space program, however mired it was in Cold War jingoism, accentuated the undeniable recognition of the interdependence and frailty of the Earth. The first-hand transcendental experience of viewing the blue ball of life floating in the great enveloping darkness, shielded by a paper-thin atmosphere has been proven to stem a cognitive shift in thinking, time and time again by astronauts and cosmonauts alike. National boundaries vanish. The conflicts that divide us become trifling and the full folly of human conceits come to bare. Just as humanity conceived instruments of death capable of exceptional self-harm, this revelation underscored our responsibility to protect this fragile biosphere and all its members emboldening the environmental and humanitarian movements of recent decades.

In the realm of science and technology, rock and soil samples brought back are still vital to lunar and planetary science investigations. Lunar surface layers serve as archives frozen in time storing records in the form of solar wind particles, the cosmogenic products of cosmic ray impacts, and meteoritic debris. The wealth of information derived from the chemical and mineralogical nature of the lunar surface has reshaped and enriched our knowledge of lunar origins, geological evolution and thus informing us of the more general processes of planetary formation. These soil layers have been studied extensively elucidating the processes critical to understanding the development of our early inner Solar System ranging from core formation to magmatic activity to solar evolution.

Spillover technological developments, the result of huge government autonomous investments pushed the boundaries of civil, electrical, aeronautical engineering and the sciences. This financial kickstart for fledgling technologies resulted in a technological trickledown which has rippled down the decades that followed. Precision matching, robotic welding and assembly, photovoltaic cells and the list goes on. For instance, Apollo Guidance Computer designed by MIT Instrumentation Laboratory was central to the evolution of the integrated circuit, forerunner to the microchip, and is regarded as the first embedded system. The guaranteed market and premium prices paid by the NASA and military in the early days of the Integrated Circuits were decisive factors in determining the success of the industry, and led toward mass-produced, low-cost chips for the subsequent personal computing and the unprecedented digital revolution.

Under the aegis of the Apollo program, we augured in the golden era of space exploration stretching till the 1980s before the traumatic Challenger incident. We dispatched engineered robotic spacecraft to the far recesses of the Solar System, conducting reconnaissance of dozens of alien worlds. From the flybys of the Mariners and Pioneers to the soft landing of the Soviet Venera 8 these probes functioned as windows into these distant worlds illuminating our understanding of our Solar System. Utilizing the gravity assist manoeuvre, the Voyager Probes took advantage of a rare alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune that occurs once every 175 years to send probes on a “Grand Tour”. These probes reshaped our view of the gas giants and have just crossed the heliopause, destined perhaps eternally to be runaways in the stellar void of the Milky Way. While manned spaceflight stalled, planetary science thrived. We currently have dozens of these robotic emissaries sending us back wondrous data daily.

Withdrawal Syndrome

Since the heydays of space exploration being buffeted by the winds of political change has become standard operating procedure for NASA. The Apollo Program inspired the generations that followed, a story of ordinary people realising extraordinary dreams. Nonetheless the widespread consensus which spawned it would prove to be an anomaly: the result of an elusive alignment of national decision-making process with the aspiration of space exploration. Amusingly for a program designed to demonstrate the superiority of the free-market system, it succeeded by mobilising vast public resources within the mechanizations of a centralised bureaucracy under government directive. Proposals had been drawn up for a more resilient human presence in cislunar space, involving more substantial infrastructure such as reusable shuttles, orbital transfer vehicles, propellant depots and permanent space stations orbiting both Earth and Moon. However, these were discarded except for a scaled back Space Shuttle program under the Nixon Doctrine. Public-Private partnership for commercial activity in space, which could have served as a bypass to the government centric control and execution of the national space program, didn’t arise either. Thus, the very bureaucracy that landed man on the moon in less than a decade, would end up stifling further manned spaceflight as the political rationale that once fuelled it evaporated.

“The discovery of America, and that of a passage to the East Indies by the Cape of Good Hope, are the two greatest and most important events recorded in the history of mankind.” ––– ADAM SMITH IN HIS WEALTH OF NATIONS, MARCH 1776

Merchants betwixt Worlds

Enterprise has always thrived more strongly in the presence of strong private and social incentives to reward risk-taking. Ming Dynasty China was a centralised bureaucratic monolith. There was little marketplace for ideas beyond those the state approved and promising ventures – such as Zheng He’s naval expeditions in the early 15th century to promote trade links across East Africa and the Indian Ocean – could be and was scuppered by imperial decree. Conservative risk averse factions in court viewed these extravagant tours as unwise wasteful expenditure expressing widespread disapproval. The succeeding Emperor Hongxi adopted a more sustainable inward-looking policy and eventually in 1525 the government ordered the destruction of all oceangoing ships. Thus, the potential of the Treasure Fleet and Ming Dynasty’s maritime pre-eminence was never fully realized.

In sharp contrast, Europe, flanked by and shoved out by the dominant Ottoman Empire to the East, comprised of many small, fragmented, weak and increasingly warring states. Thus, political geography served as an impetus to rulers who were desperate for sources of revenue especially through lucrative trade routes to feed burgeoning mercantilism at home and their ratcheting military appetite. Headstrong or obstinate (depending on how you see it) men, sponsored by the ruling class, compelled by faith, greed and grandeur would attempt to navigate the seas for alternate routes to the Indies. The greatest blundering genius of them would probably be Genoese mariner Christopher Columbus who rarely knew where he was, let alone where he was going but open the gates to the riches of the New World (or as Columbus would have you believe even on his deathbed the Orient) he did. The magic of it all is if Queen Isabella had rejected Columbus’s proposition or if Columbus himself crashed into some boulder, the ports of Europe had lionhearted men and the wealthy aristocrats required to bankroll them aplenty. Consequently, the voyage to the New World would have occurred regardless.

In the dizzying years that followed, almost anything and everything seemed possible to the conquistadors and adventurers who crossed the Atlantic and rounded Africa sustained by innovations in financial instrumentation and continent-wide market activity. The rest as they say is history, Europe plundered and got a whole new continent while Native Americans subjugated, got smallpox. These events transpired due to compelling incentives, however unscrupulous or delusional, for individuals who would end up tilting the axis of the planet in the West’s favour. About four centuries later, the Spirit of St. Louis, in lieu of Santa Maria, full flying speed – controls taut, alive and straining – would attempt to conquer the Atlantic, this time however heading back to the Old World in search of the City of Love.

The Lindbergh Boom

It was the May of 1927, a lone monoplane emerged from across the Parisian horizon. In the spartan cockpit was an obscure air-mail pilot from over 3000 miles away. As Charles Lindberg descended on the Le Bourget Field to the adulation of crowds numbering in the 100,000s, the aviation industry took flight. The historic non-stop flight across the Atlantic displayed the potential of long distance flight. In no time, Wall Streeters were banging on doors, policy makers churning out civil air safety guidelines and capital flew in as interest in commercial aviation skyrocketed. Within less than a century, a world without aviation is unimaginable.

The dreams of flight and that of private space flight are twins, conceived by similar visionaries and evolving with many parallels. Just as the Orteig Prize of $25000 motivated Charles and his backers to attempt to cross the Atlantic, the 10 million-dollar Ansari X Prize incentivised Burt Rutan’s (legendary aerospace engineer who also designed the first plane to fly around the world without stopping or refuelling) Scaled Composite backed by, co-founder of Microsoft, Paul Allen. They launched the rocket-powered SpaceShipOne from a mothership 14km up. It arced through space and crossed the Karman Line, an arbitrary line which lies at an altitude of 100km, and repeated the feat within a week kickstarting the dreams of the commercial spaceflight industry. This time it was deep pocketed billionaires spawned in the nucleus of the 21st century start-up culture who went knocking on doors as they set their gaze up to the stars seduced by the commercial potential of human access to space.

Private spaceflight reawakened the promise of manned spaceflight. Rockets require vast time, resources and expertise to be assembled, launched into space, and in the end either unceremoniously burnt up in the atmosphere or crash into the ocean as scrap metal. Imagine an aviation industry as inefficient, the only aircraft flying around would be Air Force One. The need for an inexpensive reusable vehicle has been the obvious step for the 40 years since the Apollo Era. The Space Shuttle program was conceived on that very premise, aiming to launch payloads for under $100 a pound with one launch per week on average. However, NASA never delivered and instead trapped man within Low Earth Orbit for 30 years. After each mission, the orbiter and the solid rocket boosters required extensive inspection and repairs, consequently getting to orbit remained a risky and expensive proposition as NASA struggled to translate the reusable orbiter and solid rocket boosters to tangible capex savings. The program reached an anticlimactic halt in 2011 after 133 successful flights with a payload cost of an exorbitant $10,000 per pound. Compared to the $81 million per astronaut NASA pays the Russians to send them to Low Earth Orbit on the Soyuz, the entire SpaceShipOne endeavour only cost $27 million. After selling the technology to Virgin Galactic founded by Richard Branson, Paul Allen turned a net profit and suddenly the free market economics of spaceflight appeared workable resulting in a dynamic explosion in spaceflight that government alone can never hope to mimic.

By then, real-life Tony Stark, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos, the founder of Amazon.com, had already established under the radar aerospace companies, Space Exploration Technologies Corp and Blue Origin respectively. Both were enamoured by chimerical dreams, one of multi-planetary expansion and the other of lifting heavy industry into outer space with millions living and working off-world. From having vodka shots with Russians for the purchase of ICBMs on the open market to recovering Apollo F-1 engines three miles beneath the Atlantic, these visionaries seem to have gotten immunization shots for risk that the rest of us forgot to get when we were born. Irrespective of their differences over means of fulfilling their ambitions, they agree that the final frontier proffers the solution to the quagmire we are tangled in on Earth.

Vectors of Infection

Planet-bound civilizations not only impose limitations on the material enlargement of civilization, it also places us as a species in a precarious spot. We reside in an inter-galactic neighbourhood that is dynamic armed with a couple of definite ways to sterilize the thin film of life inhabiting the surface and countless more theoretical ones. When it comes to destruction of worlds we also happen to be our worst enemy. Nations possess thousands of nuclear warheads capable of occasioning an existential catastrophe, and we are at the liberty of a fairly fragile global ecosystem as we belch greenhouse gases to fuel our ever-increasing needs and wants.

It could be argued there is a moral imperative to act on behalf of life itself of which we are at least the bearers, if not the sole possessors, to act as its dispersal vector. Life since it’s inception has reached out to cover every niche it can. Neil Armstrong’s first words on the Moon were a massive understatement, that step was as significant as the one our amphibian cousins took 400 million years ago onto land. Being a spacefaring civilization is the first step toward assuring the durability of civilization and ensuring our visibility to natural selection on a cosmological scale. This vision of making life multi-planetary was one that would transmogrify a spreadsheet into SpaceX that would in the coming years re-enact a sophisticated parody of David and the Goliath.

“After analyzing the sanctions against our space industry, I suggest to the USA to bring their astronauts to the International Space Station using a trampoline.” — RUSSIAN DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER DMITRY ROGOZIN, AFTER U.S SANCTIONS PRECIPITATED BY THE UKRAINIAN CRISIS

Draining the Swamp

In an industry brimming with middleman price hikes and literally decades-old legacy technology, SpaceX’s firmly controlled in-house supply chain and trailblazing technology has it competing as the world’s cheapest option for space delivery even besting China’s Long March’s price point. Whereas established commercial launch consortiums like International Launch Services and Europe’s Arianespace once scoffed at the California upstart, the success of SpaceX has them rapidly scrambling to cut their own launch costs and pursue reusable rockets of their own as their decade long military-industrial complex business model heads for the dust heap of history. For years, the US government had relied on two major aerospace companies—Boeing and Lockheed Martin, along with their joint venture, United Launch Alliance (ULA)—for domestic launches. They made their money through pulling strings at Capitol Hill and cozy military and government relationships for vastly inflated sole-source contracts ( SpaceX will sue the Airforce over this to be certified for military and intelligence payloads) costing an average of $380 million per launch. Traditional aerospace companies tend to outsource their production to sub-contractors and these contractors in turn sub-contract to layers further down the supply chain, resulting in massive overheads. Their operations were bloated and technology were stale hardly distinguishable from their Soviet and now Russian counterparts. In fact, ULA’s Atlas III and later the Atlas V, were powered by Russian RD-180 first-stage rocket engines. That’s right US defence satellites, which probably snoop and spy on Russia, can’t be launched without the Russians themselves. SpaceX brought the tsunami - organizational ethos of Silicon Valley: lean manufacturing, vertical integration, flat management to this stagnant swamp of an aerospace industry. Engendering the tectonic shifts in propulsion technology, spacecraft design and reusability requisite for this tsunami to take form, however, has been anything but easy.

It’s tough

For 6 long years, a good 4.5 years more than expected, SpaceX wrestled with the chains of gravity. Three times, from the spring of 2006 to the summer of 2008, it had seen the lean, single-engine Falcon 1 rocket lift off from an atoll in South Pacific only to fail to reach orbit. By then Elon Musk had sunk hundreds of millions of dollars in developmental cost, racking up personal debt and both his companies Tesla and SpaceX had little revenue to show for it. On September 28, 2008, a cash-strapped SpaceX executed its first successful launch becoming the world’s first privately built rocket to achieve Low Earth Orbit. In SpaceX’s darkest hour as it struggled to meet payrolls, NASA ushered in the dawn offering SpaceX a $1.6 billion Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) contract to make 12 deliveries for them to the International Space Station. This infusion of cash reinforced the capital-intensive transition from a single Merlin-engined Falcon 1 rocket to the much more exigent Falcon 9 rocket and the Dragon Space Capsule. What followed were rapid succession tests and iterations to achieve cadence with the Falcon 9. Milestones were cleared one after another. First privately funded company to successfully launch, orbit, and recover a spacecraft. Check. First to dock and berth a spacecraft to the International Space Station. Check.

Elon’s Reusable Ark

Concurrently the reusable launch system technology development program would evolve to become the focal point of SpaceX’s energy and resources. The low-altitude, low-velocity hover/landing test vehicle, Grasshopper and the subsequent vertical-launch & vertical-landing Falcon 9 Reusable Development Vehicles served as a development testbed for SpaceX’s first propulsive landing of an orbital rocket’s first stage on land in December of 2015. The audacity of the concept and breakneck pace of development has been breath-taking to witness. On April 8, 2016, Falcon 9 Flight 23, delivered the SpaceX CRS-8 cargo on its way to the International Space Station while the first stage conducted a boostback and re-entry manoeuvre over the Atlantic Ocean. Nine minutes after lift-off, the booster landed vertically on an autonomous drone ship aptly named ‘Of Course I Still Love You’, 300 km from the Florida coastline, achieving another long-sought-after milestone for the SpaceX reusability development program. SpaceX has indicated that they are now able to consistently “reenter from space at hypersonic velocity, restart main engines twice, deploy landing legs and touch down at near zero velocity”. To date, SpaceX has successfully brought Falcon 9 first stages back to Earth 21 times during orbital missions, and four of those landed boosters have flown again. Though engineers initially shelved the idea, they now intend to develop the technology for a scorching re-entry to extend reusable flight hardware to second stage. This is a more daunting technical challenge considering the vehicle is travelling at high delta velocity usually so that the payload can reach geostationary orbit.

Invisible Pressurised Glove

2018 is starting out with a bang (not a literal one I hope) as the current phase in SpaceX’s journey culminates with the maiden launch of Falcon Heavy happening this week. Between the mission in the Dragon 2 to the ISS flown under NASA’s Commercial Crew Development Program marking the first manned launch from US soil since the space shuttle was retired in 2011 (it’s competing against old guard, Boeing’s CST-100 Starliner) and the slated plans of sending two space tourists on a free return trajectory around the Moon, this year is shaping up to be hopefully the most riveting year in the SpaceX saga. To realise his visions of a sustainable human civilization on Mars, Musk is now diverting resources into a next generation rapidly reusable spacecraft named as ‘BFR’ ,which is capable of producing an astounding 52 meganewtons worth of thrust at sea level (That’s right enough to lift off with an adult blue whale as payload and land back with it). But it gets better, this colossus of a rocket will have the lowest marginal cost per launch accounting for reusability of any spacecraft ever. This could in theory lower the cost of lifting material into orbit by an entire magnitude. The cost of the propellant (fuel/oxidizer combo) on the BFR is absurdly low as the Raptor engines, currently under development, only rely on liquid oxygen and densified liquid methane. As the cost of placing and maintaining capability in space falls dramatically, it transforms sense of possibility providing a platform to leapfrog the feasibility of every endeavour in space. The presence of this robust commercial market, in turn, through economies of scale, would result in a further fall in the cost of access to space. Suddenly the heavens themselves, appear pedestrian.

“Earth is the cradle of humanity, but one cannot remain in the cradle forever” — KONSTANTIN TSIOLKOVSKY, FROM A LETTER WRITTEN IN 1911

Lighthouse for Skywalkers

Here is the wonderful part. Just as in the ports of Europe 500 years ago, where private and social incentives galvanized men with heartwood of oak to sail the Atlantic, so too it inspires the innovators of today to spearhead through the atmosphere into orbit. SpaceX is not alone. Blue Origin has successfully completed the fifth launch and landing of the very same suborbital New Shepard rocket and crew capsule. Bigelow Aerospace has already launched inflatable space station modules into Low Earth Orbit. Orbital ATK has made deep investments in developing its on-orbit robotic satellite servicing capabilities to tackle space logistics challenges. NASA in partnership with the private firm Made in Space has installed a 3D printer customised to operate in microgravity in the ISS, this opens the door to on-orbit manufacturing using the very materials that in the future might be sourced in space. Companies such as Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries are beginning work on asteroid mining capabilities to prospect and extract materials, minerals and even synthesise propellant through processes such as electrolysis in space. These headways if proven sustainable would eventually mature to fully fledged industries. These are few of the multitude of pathfinders in the bottom-up emergent order which is redefining the space industry (if I talk about all these endeavours with more depth, I would be suffering from Alzheimer’s by the time I would be done but thankfully the cure for it would have been discovered as well). It is no wonder why analysts at the Bank of America Merrill Lynch expect the private space industry, which is valued at $350 billion right now, to octuple to nearly a $2.7 trillion valuation in the next 30 years as one realises we are sitting on the precipice of an entrepreneurial metamorphosis.

The Scarred Knight

To a generation that felt the risk-averse sclerotic government tethered space program had failed them, their dreams of spaceflight might be actualised. You need look no farther than compare the development of the Falcon series of vehicles with the NASA Ares 1, Ares 5, and now the Space Launch System. NASA is currently betting on large appropriations in the coming years that will enable it to undertake a massive, Apollo-like undertaking to set sail for Mars. However, it has not been able to command that kind of budget since the 1960s.

The fundamental barrier is institutional. The space agency has been squeezed and suffocated by parochial Congressional meddling for years. The political establishment of today neither has the will nor the resolve to pursue a concerted long-range initiative towards manned spaceflight beyond the Low Earth Orbit. From the days of the Raegan Administration Star Wars program, where space architects dreamt of kinetic and particle beam weapons and all kinds of bedlam, flip-flop has been the name of the game for the mercurial American Space Policy. Take this century as an exemplification, first there was the George Bush era Constellation program that was supposed to develop a sustained human presence on the Moon but instead America categorically decided it’s better to have a sustained human presence in Iraq. Upon taking office, President Obama declared the program to be “over budget, behind schedule, and lacking in innovation” cancelling it and redirecting NASA’s focus to sending people to an asteroid, and then once again set its sights on a human Journey to Mars. Then Trump’s Space Directive 1 (Since Trump’s inauguration NASA still doesn’t have a new administrator - MAGA) reshuffles NASA’s human exploration priorities, yet again, back to the Moon calling for the establishment an Earth-to-Moon infrastructure, including a permanent presence on the moon.

US space policy has vacillated and dithered like the Spiderman movies, every few years there appears to be a new one resulting in a cul-de-sac of underfunded and cancelled programs. There isn’t a long-term goal, a lodestar to help align short term missions to build momentum forward. Instead when Congress hits reset on the agency’s funding every year, it plays havoc with space projects that can take time to get off the ground resulting in lack of financial stability. Thus, budgetary and time pressures has given rise to a “go as you can afford to pay” framework granting little margin to deal with unanticipated hitches that arise during design and development. Overcommitted in terms of program obligations relative to resources available, the Challenger and Colombia disasters proved to be merely symptomatic of these underlying issues. Private entities like SpaceX have outmanoeuvred behemoth national space agencies such as NASA just as the Europeans outplayed China in a geopolitical game they didn’t even know they were players in. Despite these intrinsic problems, NASA admirably hasn’t abdicated its mantle at the boundaries of science and still manages to be as relevant as ever in fulfilling its promise of furthering human access to space. NASA will continue to be the hero human space endeavour needs, but not the one it deserves. A giant without whose shoulder to stand on, the commercial space industry would flounder.

Much of SpaceX’s base technology is in fact rooted in lessons from NASA’s own research and development over the decades; a testament to how government and industry can leverage expertise and resources effectually. NASA’s role in nurturing the nascent private spaceflight industry through public-private partnerships in the form of Commercial Resupply Service contracts, whereby cargo and supplies are delivered to the International Space Station (which saved SpaceX), and the multiphase Commercial Crew Development program can’t be understated. Through its commercial cargo and crew programs, NASA has enabled home-grown private companies like SpaceX, Orbital ATK, Boeing, and Sierra Nevada to develop a modern fleet of spacecraft to provide safe, reliable, cost-effective access to Low Earth Orbit whilst reaping cost savings for the taxpayer. The supply services offered by SpaceX and Orbital ATK have cost NASA two to three times less than if NASA had continued to fly the space shuttle.

The Heavenly Homestead Act

As the commercial arena of space swells in the coming years, formulation of sound policies to foster the innovations that will further lower space access costs will be integral in determining the revolutionary potential of private space industry. Not just NASA, governing bodies utilizing their purchasing power to provide base load demand for incipient space services and invest in resilient civil space infrastructure. Long term prospects won’t be solely determined by government based support and demand. It will have to be augmented by the commercial sector as well. Thus, policy makers need to set appropriate standards for accepting risk, encourage dynamic competition in the market, and introduce a transparent, well-structured, and minimally burdensome regulatory framework. This could be further strengthened or reinforced if carried out in the international setting as more nations such as Japan, China and India seek to amplify their presence in Outer Space. More ideally it would be awesome, if the spirit of international collaboration and cooperation manifest in efforts such as International Space Station are extended into commercial space efforts as well.

United Corporations Space Command

Cross-pollination of ideas has been the linchpin of human advancement. If genetic diversity and ecological variety are healthy for a biosphere, problem diversity and solution variety is tantamount for the innovations that helps us address all sorts of modern hurdles and bottlenecks. Humanity lies at the base of a steep learning curve. As intellectual connections within and across disciplines proliferate, and as we leverage our ever-growing collective capacities to crunch through mountains of data, paradigm shifts in the models and theories that govern our contemporary thought are bound to happen. This process of challenging deep assumptions embedded in our thinking and society is integral to humanity’s growth as a species.

Every paradigm has limits and else we confront them progress stalls and civilization would be suspended in stasis or worse yet stagnate and degrade. State funding lines up better with the costs and time horizons of fundamental science often without applications in view. The pay offs and return on investments too far off and uncertain and thus undesirable for those with profit motive. From Fleming’s discovery of penicillin, to recent examples of blue-skies research such as the Large Hadron Collider, at CERN in Geneva or the Human Genome Project unfettered, fundamental, curiosity-driven research is essential for flourishing human potential. Revolutions in science that shatter paradigms are spun out of such science and state money is traditionally the spinner. However, in America, for example, for the first time in the post–World War II era, the federal government funds less than 50% of the basic research carried. State patronage has flattened due to austerity strangling research budgets and has become conservative due to public pressure to show value for money. Interestingly, here too corporations are superseding nations by increasingly investing in moon-shot thinking.

Audacity is what is missing in our public arenas. It’s what stokes public confidence in the leadership and what produces discoveries that uproot the norms. Current anti globalist, xenophobic and insular protectionism sentiments are inevitable response of a populace subject to short term small minded initiatives in face of growing uncertainty, complexity and entanglement of society. An audacious international space program empowered and complemented by the private sector would instil and inspire a shared human vision like no other. From the Knights of Templar to Coco-Cola, private corporations have always had little to no regard about national boundaries (oft for self-serving reasons). In a somewhat similar vein, I believe private space enterprise as they collaborate across borders would similarly disregard nationalistic divisions and serve as a bridge to a universal percipience of hope and confidence, one which nations have foundered to realise, by pushing the boundaries of human experience itself.

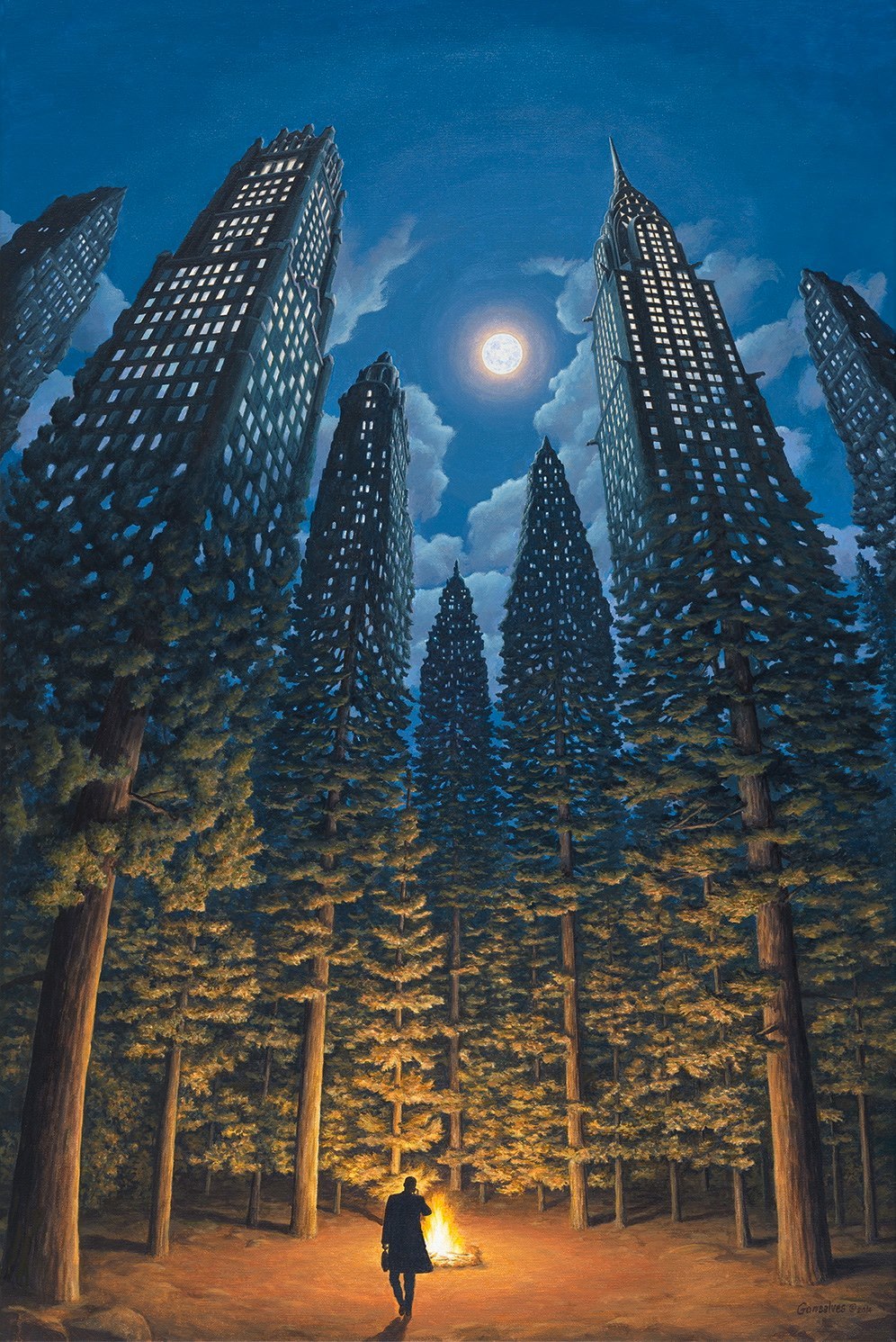

Cosmic Cathedrals

If asked, “What happened in 1492?”, most would answer ‘ah I know Columbus discovered America’. Not many of us would be spewing details about how England and France signed a peace treaty, neither would we be debating about the implications of the death of Lorenzo de Medici: the most powerful patron of the Renaissance, nor would we be conversing about the papal conclave in the Sistine Chapel. A robust space initiative of our time will be in my contention, a standing monument of the 21st Century for posterity. One that cannot be encapsulated in a mere cost/benefit analysis. A millennium from now, we are not going to be remembered for which faction came out on top in Syria, or Crimea, or wherever. Our epoch will be instead remembered hopefully for when humanity first ventured off the shores of the uncharted interstellar ocean and saw it from afar as a wanderer, lost amongst the stars.

APPENDIX I

This is but a cursory look into NASA’s effort in the field of Space Medicine that I wrote but don’t feel like deleting

Space flight has always been an intrinsically risky endeavour, however as we attempt to sustain long-term presence in orbit and further out into the Solar System, the health risks posed to humans are manifold. Microgravity as experienced on the ISS, has undesirable effects on various bodily systems especially the circulatory, musculoskeletal and immune systems. Fluid distribution is the challenging one. On earth, gravity body fluids tend to pool in the legs. To counter this effect of gravity, veins in human legs have evolved valves that open and close to assist blood circulation back up to the heart. In orbit, however, blood pressure equalizes and fluids tend to reverse what they do on Earth and pool toward the head. This shift of blood and other fluids toward the head precipitates many problems. The brain’s hypothalamus interprets its increased blood supply as an increase in total fluid volume rather than simply a redistribution. In response to this misperception, the brain signals the kidneys and other organs to decrease the volume of blood and other fluids by pulling water out through increased urination. The decrease in fluid volumes is not in itself a problem, but the process in turn triggers losses of minerals such as calcium, which leads to loss of critical bone minerals. Other complications caused by this issue include increased excretion of calcium from your bone coupled with dehydration resulting in formation of kidney stones and greater possibility of osteoporosis-related problems when returning to Earth.

Biomedical research conducted in space is essential for us to gain a better understanding of the health risks of long-duration spaceflight and to develop ways to minimise and mitigate these risks. This is where NASA’s [Human Research Program’s] (https://www.nasa.gov/hrp) findings have been paramount in bridging our knowledge gaps on the effects and impacts of space flight on the human body. One of its major successes achieved over years of trial and error study has been a solution to the physical deconditioning explained above whereby bones lose minerals, with density dropping at over 1% per month. These days astronauts go through a 2-hour exercise regime everyday involving high intensity exercises on treadmills, cycles and resistive exercise devices. Applying resistance and pressure on the bones and muscles assists the rebuild of bone lost. As scientists learn more about the various risks, some risks grow in significance. For example, cancer was believed to be the most significant risk associated with radiation exposure (Galactic cosmic rays and solar energetic particles), but research has shown that central nervous system effects such as impaired motor skills and seizures may also be a major concern. Building risk models for radiation’s long-term effects have also been challenging due to the small sample size of astronauts.

NASA still faces significant challenges and uncertainties in ensuring the safety of crew members on a possible human mission to Mars or deep space out of the protective magnetosphere of our planet for a prolonged time. Deep space presents a more unforgiving environment in terms of radiation and isolation from Earth (it takes on average 14mins for light to reach Mars – that’s 28mins of round-trip time latency for information) compared to Low Earth Orbit. Psychosocial stressors have also been identified as one of the most important impediments to optimal crew morale and performance even in the ISS, where every minute has a timeline and NASA leaves nothing to chance walking astronauts through the day without need for improvisation. Thus, the scope of the challenges and demands that face astronauts in deep space increase dramatically as astronauts will have to transition from a command-centric model to a more crew centred one which may result in greater tensions and psychological issues over prolonged periods of time in an isolated alien environment. Now these perils to both physical and mental faculties sound frightening but NASA is investing substantial amount of resources to mitigate these risks. Significant brainpower is being dedicated to discovering the best methodology and technologies to support safe, productive human space travel. Artificial Gravity produced by centrifugal forces has been proposed as a possible solution for the weightlessness problem, lightweight radiation shielding materials are being considered and even novel propulsion technologies to reduce transit times. Effective mitigation of the risks to human health posed by long duration missions is a significant undertaking that can only be achieved with effective management and collaboration across various disciplines such as life sciences, engineering, nutrition, material and social science to engineer effective and human solutions. By continuing to leverage assets through national and international collaborations just as NASA has, I am confident human spaceflight will only get safer with time.

Thoughts?

This is my first time writing in forever so let me know how to improve. Is it too long like Bladerunner 2049 or too short like Tyrion Lannister? Maybe you have a different perspective on the topic? I would love to here your thoughts down below.

Weigh the Scales