Natura Naturans

On the mountain they felled my trunk

All my schemes come to ‘naught

Without shame a troubador am I

I know trouble, my brothers!

Yunus, comes and finds no joy here

The tree will never grow

In this fleeting existence no one remains

I know trouble, my brothers!

––– Yunus Emre, Troubled Waterwheel // Dertli Dolap

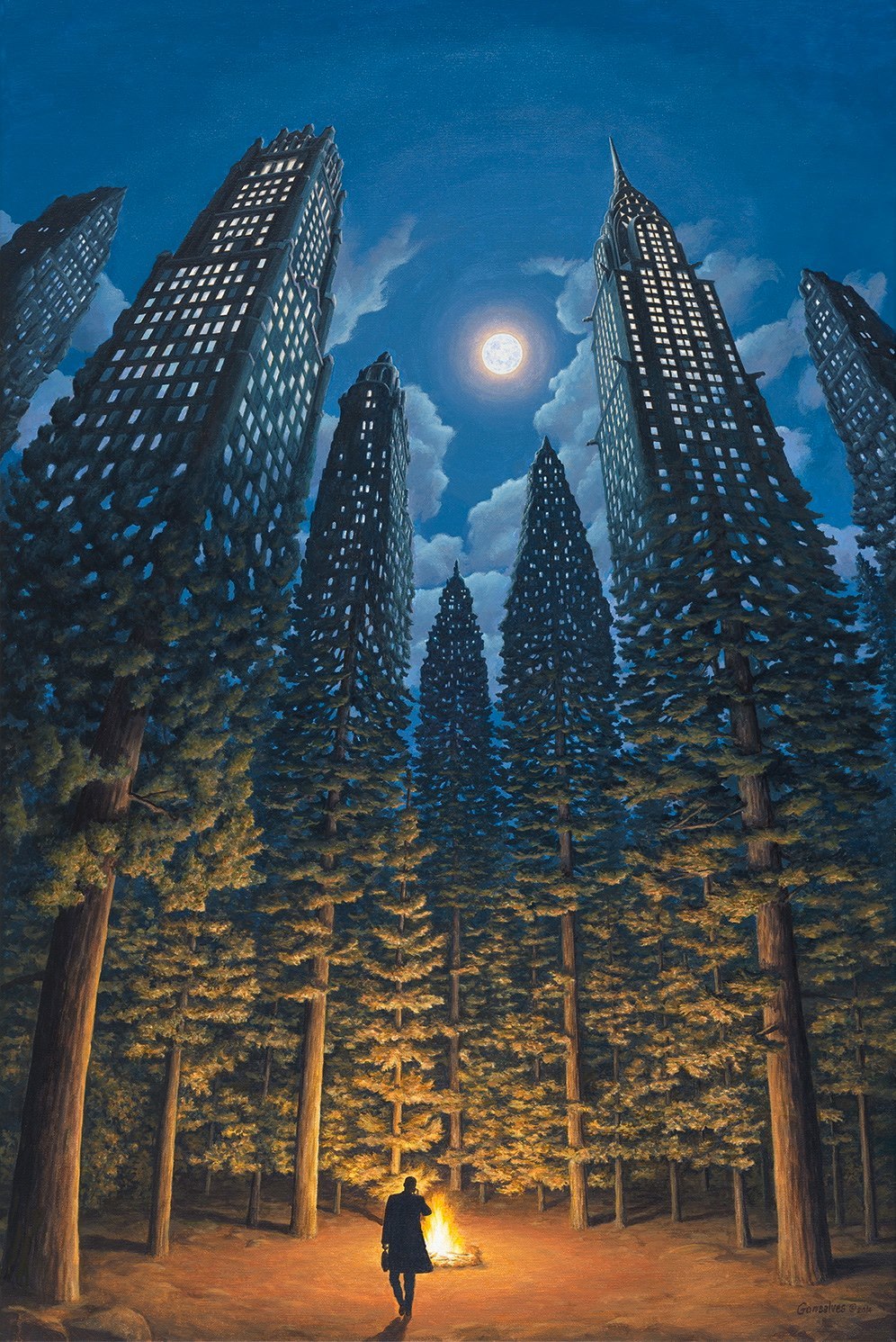

In a subcontinent mired in contradictions: a colorful cacophony of splendor and squalor resounding a mere paper’s thickness away and more often than not appear as one and the same. A mere snapshot would do no justice to the unabated circus of life and death that simply overwhelms an unready spectator. Where the profane struggles to assemble anything that resembles order. However here purposeful rectilinear urban blocks emerge against the encircling chaos of wayward dirt paths and mismanaged infrastructure that had come into existence piecemeal, every piece in a violent hurry for some one man’s purpose. Euclidean geometry willed against the organic dynamics of non- linearity. Perhaps this could be explained away as the conjurings of the bureaucratic nucleus cloistered at the heart of the borough. Yet a distant pulse drowns this intuition. Averting one’s gaze few miles south uncovers the underlying, both in the literal and figurative sense, beat of the heart that this urban edifice drums along to. A topography of open wounds unfurls. Towering terraced bowls stagger into a downward descent pursuing veins of lignite. Relics of a lost geography; what were once contours of the land displaced by retaining walls and stabilized slopes. The superconstruct of detritus stands silent, witness to 2600 ton of German engineering ingurgitating through its underbelly as the various industrial mechanizations reshape this landscape not unlike how an artisanal potter molds malleable clay into the form he sees fit at the nearby Night Bazaar. Paired with a thermal power station built under the Indo-Soviet assistance programme it was the realization of the Nehruvian vision of an energy bridge for the Indian economy into the future. Nonetheless, the barren blanched lunarlike canvas serves only to betray the scope of mankind’s uneasy and disquieting relationship with nature. It’s a revelation of the unrestrained violence required to assemble our supply chains and markets: a form of decentralised planetary disassembly, mortal structure derived from perpetual discord. A reflection of the wider metabolism of our contemporary society that has been hijacked by the inarticulable forces that lay beneath. Thus, we encounter the grand dissonance that lies within the heart of modernity that transcends far beyond the mere spatiality of subterranean shafts and bureaucratic warrens of a small township, where I was born into this implicit modern covenant: one forged through the channelling of Nature’s very own laws upon Nature through the hands of Man.

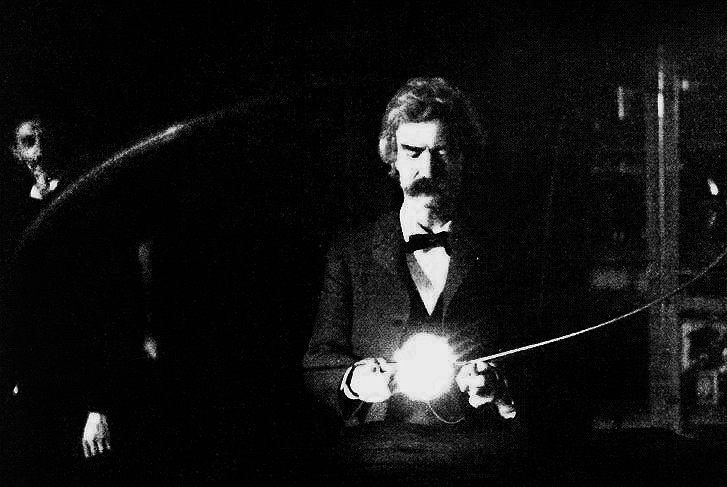

Man’s recasting of the natural world cannot be merely understood with regards to the implements of technology at his disposal, but instead through the framework that enables such manipulation, for the former would be confusing the armaments of war with the essence of war in itself. Observe in the final chapter of “Discourse on Method”, as René Descartes pronounces the technological aspect of the Cartesian project that through ”knowing the force and action of fire, water, air, the stars, the heavens, and all the other bodies that surround us, as distinctly as we know the various crafts of our artizans, we might also apply them in the same way to all the uses to which they are adapted, and thus render ourselves the lords and possessors of nature.” Natural philosophy was no longer a matter of mere contemplation no longer satisfied with merely embracing and unveiling the secrets of the world, but at making them serviceable to definite ends, set to reconfigure the human condition. A rupture with pre-existing relations with Nature awaiting to be staged. An interrogation of nature under the torture of instruments of science for subsequent reconfiguring of these very forces as inputs into human civilization. Seminal thinker Martin Heidegger in “The Question Concerning Technology”, referred to the tendency such a mode of inquiry has wrought within the hallways of modernity as Gestell translated frequently as enframing. Referring to interrogation of nature in modern physics, Heidegger apprises that “Because physics, already as pure theory, requests nature to manifest itself in terms of predictable forces, it sets up the experiments precisely for the sole purpose of asking whether and how nature follows the scheme preconceived by science.” Thus, such a process “drives out every other possibility of revealing” or looking at things, imposing, upon the multiplicity of natural phenomenon from that of a flowing river to the icy tundras, an ordering he called “standing reserve”. The richness of the natural world reduced as resources to be put to man’s service, a river to be dammed, a tundra to be drilled, potentialities to be captured. Heidegger’s thought deepens with the conception of the Fourfold. [H]uman being consists in dwelling and, indeed, dwelling in the sense of the stay of mortals on the earth. But ‘on the earth’ already means ‘under the sky.’ Both of these also mean ‘remaining before the divinities’ and include a ‘belonging to men’s being with one another.’ By a primal oneness the four—earth and sky, divinities and mortals—belong together in one. Earth is the serving bearer, blossoming and fruiting, spreading out in rock and water, rising up into plant and animal… The sky is the vaulting path of the sun, the course of the changing moon, the wandering glitter of the stars, the year’s seasons and their changes, the light and dusk of day, the gloom and glow of night, the clemency and inclemency of the weather, the drifting clouds and blue depth of the ether However, what is to occur when these apparatuses of capture are directed at forces closer to home upon man himself.

Just as Prometheus thrust his hands into the Empyrean to recast divine fire for the utility of man, humanity brought about tidings of his own subsequent downfall in his attempts at individuating himself from nature through the application of its very own laws. Pascal would succinctly express the sense of alienation such an enterprise invokes in his “Pensée” for “All bodies, the firmament, the stars, the earth and its kingdoms, are not worth the smallest mind, for a mind knows them, and itself, and bodies know nothing.” Such a conception of a vacuous desacralized world only serves to reimagine man, as a stranger to the world, who fulfils his station as sovereign in his search for knowledge; a prime mover subject to nothing more eminent, bestriding upon the natural world as Colossus. Man’s own nature was thus to experience an axial shift as the essence of the tools he built to control Nature’s forces seeks to subsume human agency itself. “The Lord of the World is becoming the Slave of the Machine, which is forcing him — forcing us all, whether we are aware of it or not — to follow its course. The victor, fallen, is dragged to death by the raging team.”, Oswald Spengler proclaims in Man and Technics. Just as the tools of Homo Faber takes its form from the shape of the hand, the tools in turn informs and shapes us. We might have domesticated wheat through the birth of agriculture but that in turn domesticated us. The imperial gaze of technology redirected upon himself. In Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Ode, Inscribed to William H.Channing” man is atomised into the alpha versions of what these days economic systems term human capital.

“The horseman serves the horse,

The neat-herd serves the neat,

The merchant serves the purse,

The eater serves his meat;

‘T is the day of the chattel

Web to weave, and corn to grind;

Things are in the saddle,

And ride mankind.”

––– Ralph Waldo Emerson, Ode: Inscribed to William H. Channing

Here tragically it is mankind that is to be ridden, Homo Faber reduced to the “standing reserve” servicing the role of reproductive organs of our tools and propagating the assemblages with the shadow world of tools. These tools however merely express the social forms capable of using and creating them as such mankind’s attempts at transcending nature through this mode of creation are but Pyrrhic victories. Man becomes subject to his own modes of capture: a stranger to himself. Entrapped within a disenchanted illusory mirrorhouse of his making in his retreat from Nature, one wonders the chances the Nature that he has forsaken augurs for escape.

Nature offers the possibility of reintroducing the sacred within our midst integrating the sensual realities of older traditions of consciousness to pierce through the illusions of modernity. Native Americans named the cannibalistic spirit that deludes us into sapping and enframing the life-force of all beings and systems of Gaia: Wetiko. Such a spirit they claim blinds an individual through illusion from recognising the interdependent and enmeshed nature he finds himself in beyond the poles of such dichotomies such as Man & Nature, subject and object. Henry David Thoreau in Walden prominently declared, “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation. What is called resignation is confirmed desperation. From the desperate city you go into the desperate country and have to console yourself with the bravery of minks and muskrats. A stereotyped but unconscious despair is concealed even under what are called the games and amusements of mankind.” (Thoreau) Henry David Thoreau in Walden speaks to men haunted by just such a spirit of Wetiko masked and a cause of disillusionment and ennui. In what is ostensibly a travelogue, Henry Thoreau takes a boat trip north along the Concord River in “A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers” running off on the most erudite digressions regarding the fecund tapestry that is sensual experience “ We need pray for no higher heaven than the pure senses can furnish, a purely sensuous life.”, he proclaims , ”Our present senses are but the rudiments of what they are destined to become. We are comparatively deaf and dumb and blind, and without smell or taste or feeling. Every generation makes the discovery, that its divine vigour has been dissipated, and each sense and faculty misapplied and debauched. The ears were made, not for such trivial uses as men are wont to suppose, but to hear celestial sounds”. For Thoreau, the depths of conscious sensory experience assist in the distillation of sacred truths from the “slumbering subterranean fire” that is the natural world. Unlike his close friend Ralph Waldo Emerson and fellow Transcendentalist, Thoreau erected no transcendental barriers or higher reality to mediate this process of clear wide-eyed contemplation.

Necessary, however, was the active cultivation of one’s receptivity to the beauty of Nature for Henry David Thoreau was akin to the act of “nature looking into nature with such easy sympathy as the blue-eyed grass in the meadow looks in the face of the sky”. Thoreau aspired to scale Olympian heights by grasping the theological character of the interface between our senses and nature for he believed man need not only to be spiritualized but “naturalised on the soils of the earth”. Thus one would be able to “see, smell, taste, hear, feel, that everlasting Something to which we are allied, at once our maker, our abode, our destiny, our very Selves; the one historic truth, the most remarkable fact which can become the distinct and uninvited subject of our thought, the actual glory of the universe; the only fact which a human being cannot avoid recognizing, or in some way forget or dispense with.” The senses we utilize to engage and navigate the across the vacuous meaningless husk of materiality – exemplified in “the mass of men”, trapped within the spider webs of their conscious experience. Widen ajar one’s aperture of awareness and the very same apparatus of sensory perception unleashes a combinatorial implosion into Oneness as our sensory faculties parse the encodings of divinity layered within the hidden seams of natural phenomena.

“Go round, come round, come round, O distant time

Come round, call back my heart

Come round, call back my heart

Birds, bugs, beasts, grass, trees, flowers

Teach me how to feel

If I hear that you pine for me, I will return to you.”

— The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter, A Celestial Maiden’s Song //「天女の歌」

There is a philosophical thought experiment supposedly posed by George Berkeley that goes along the lines of “if a tree falls in a forest and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?” Often consensus coalesces around the conclusion that though such a tree falling may cause tremendous vibrations of air but would not make sound for there are no ears to hear.Berkeley’s own answer to this riddle however rests upon the perception of the infinite spirit itself one that perceives in the absence of anyone else. “All the choir of heaven and furniture of earth - in a word, all those bodies which compose the frame of the world - have not any subsistence without a mind.”. Here once again man grasps the divine purpose through the sensory world resting upon the Mind as the pre-configuring node upon which the phenomenon of the world rests. Such is also I would attest the nature of the descent of consciousness within society - it happens unperceived to some but resoundingly loud to those attuned to such change. However just as imperceptible is the silent germination and gestation of consciousness that follows within the collective tributaries of our mind. As a species the foundry for the artefacts of escape exists within us. In the clearing between our neural synapses where the stuff of dreams are forged. That twist in our collective neural pathways that plays make believe. The foundation of the human psyche. In our amphibious traversals in the twilight zone between these coexisting planes of the Mind and the Terrestrial. The unfolding of conscious experience, the Phoenix as the re-expression of its ashes. “What is needed is care; a great deal of patience; and the laying aside of many preconceived opinions, wishful dreams, and the blind sway of demand” as Jean Gebser puts it.

Weigh the Scales